ENVIRONMENTAL ICON JOHN MUIR’S SECRET WHITE SUPREMACIST CABIN: 2 OF 2

JOHN MUIR SAID HE SHARED 'IMMORTAL SOUL SYMPATHY' WITH WHITE SUPRMACIST HENRY FAIRFIELD OSBORN. OSBORN’S MOUNTAIN-TOP CASTLE COMPOUND IN NEW YORK’S HUDSON VALLEY SHELTERED MUIR WHILE HE WROTE TWO BOOKS. IT ALSO HELPED SPAWN HITLER AND NAZI GERMANY.

John Muir (second from right) seated next to the man who wrote forwards for “Hitler’s Bible,” Henry Fairfield Osborn (c), with Osborn’s family including wife Lucretia and daughters Josephine and Virginia at Vernal Falls, Yosemite National Park, 1910. Photo Credit: University of the Pacific.

THE FREE LANCE NEEDS YOUR DONATIONS TO SURVIVE. DONATE HERE.

Henry Fairfield Osborn first met John Muir during Muir’s 1893 visit to the East Coast. Osborn was 36; Muir 55. Muir’s editor and friend, Robert Underwood Johnson, introduced them, according to the Sierra Club. Muir visited Osborn again in 1898. That time Muir stayed in what he called a “charming home” on the Castle Rock estate.

“A servant brings in a cup of coffee before I rise,” he wrote his wife, Helen, in a letter dated Nov. 4.“I am enjoying a fine rest, I have ‘the blue room’ in this charming home, and it has the daintiest linen and embroidery I ever saw.”

The Osborn family visited Muir in California 12 years later in 1910. Muir took the Osborns hiking in the Sierra Nevada mountains. A photograph from the trip captures Muir, Henry Fairfield and wife Lucretia, their daughters Josephine and Virginia, posed at the base of Vernal Fall, Yosemite National Park.

Muir went back to the East Coast and stayed with the Osborns at Castle Rock again in 1911 . He settled into a cabin on top of the same mountain as the Osborn castle but on the opposite side of the mountain’s two-pronged summit on June 21.

Muir wrote fellow Naturalist icon John Burroughs from the cabin July 14.

I am at a place that I suppose you know well, Professor Osborn’s summer residence at Garrison’s, opposite West Point…. where I will remain until perhaps the 15th of August, when I expect to sail.

I am now shut up in a magnificent room pegging away at that book, and working as hard as I ever did in my life.

An essay Osborn wrote, first published in a 1916 Sierra Club newsletter and reprinted in his 1925 book, Impressions of Great Naturalists, adds more detail to Muir’s 1911 visit to Castle Rock.

John Muir's incomparable literary style did not come to him easily, but as the result of the most intense effort. I observed his methods of writing in connection with two of his books upon which he was engaged during the years 1911 and 1912. He came to our home on the Hudson in June, 1911, after the Yale Commencement, where he had received the degree of LL.D. on June 21. He brought with him his new silken hood, in which he said he had looked very grand in the Commencement parade. On Friday, June 21, he was established in Woodsome Lodge, a log cabin on a secluded mountain height, to complete his volume on the Yosemite. Daily he rose at 4:30 o'clock, and after a simple cup of coffee labored incessantly on his two books, The Yosemite and Boyhood and Youth….

He remained at Garrison for more than two months, writing his Boyhood and Youth and his Yosemite, and I have just decided to erect a tablet at the log cabin where this work was done and to name the cabin John Muir Lodge.

Letters between Muir and Osborn document the close bond the two men shared.

Responding to an invitation tendered by Henry Fairfield’s wife Lucretia to visit Castle Rock again in the summer of 1913, Muir summed up their relationship as “immortal soul sympathy.”

Warm thanks, thanks, thanks for your July invitation to blessed Castle Rock. How it goes to my heart all of you must know, but wae's me! see no way of escape from the work piled on me here—the gatherings of half a century of wilderness wanderings to be sorted and sifted into something like clear, useful form. Never mind—for, anywhere, every-where in immortal soul sympathy, I'm always with my friends, let time and the seas and continents spread their years and miles as they may.

A letter from Muir to Osborn dated two weeks later ended with

The pleasure of my long lovely Garrison-Hudson Castle Rock days grows only the clearer and dearer as the years flow by. My love to you, dear friend, and to all who love you.

It was Muir’s way of saying goodbye. He died a year later, in 1914.

I visited more than a century later. It was empty and long-abandoned. No “tablet” commemorated it but the John Muir Lodge still stood.

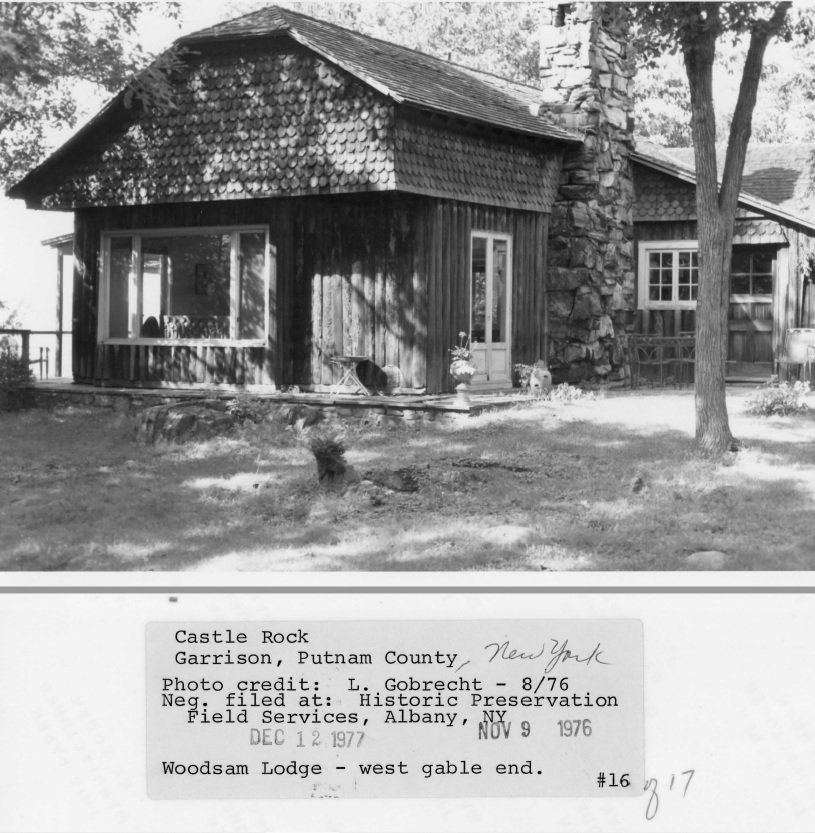

Before they sold it, the Osborn family successfully applied to the National Park Service to have Castle Rock placed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1977. After describing the Osborn castle itself, the application details “other structures.” These “include Woodsome Lodge, a small, frame retreat cabin of rustic design. It is located a few hundred yards northeast of the main house and is sited on its own promontory with a vista oriented to the north. “

Excerpt from application to have Castle Rock added to the National Register of Historic Places. US Dep’t of Int.

This precisely described the cabin I saw, and photographed. Any question is put to rest by photograph 16 of the 17 numbered photographs included in the application documenting the estate for the National Register of Historic Places. Photograph 16 depicts “Woodsam [sic] lodge—west gable end.”

The best thing about the 2,000 square-foot John Muir “cabin” was the view from the back porch, next to the hot tub. The view was like nothing I'd seen in years of tramping the Hudson Highlands. It was a grand view, revealing the Hudson River and the cliff-studded mountains surrounding it in all its rugged glory.

The great stone fortress that is West Point stands across the river, ringed with the western mountains of the Highlands in the distance behind it. Looking to the north, the view is straight up the river with the sheer cliffs of Storm King and Breakneck Ridge diving steeply into it from both sides. Freight trains run the tracks on the west side of the river bank. They look like model trains, slinking along the rocky shoreline far below.

Henry Fairfield’s father, W.H., and Church knew what they were doing when they selected this spot for Castle Rock. It is unquestionably the best view in the Highlands. Muir must have loved this signature, singular view. It is easy to imagine him sitting somewhere in the cabin beside a window or under a tree on the mountaintop outside and writing, looking up now and then to drink it all of nature’s majesty in between sips of coffee.

Meanwhile, Muir's patron was at work inside his castle, weaving pseudoscientific tales that inspired Nazi genocide.

Henry Fairfield Osborn composed or contributed to 940 titles in the field of natural sciences over his long 78-year lifetime, and he usually did his writing at Castle Rock, according to the Osborn family’s application to add Castle Rock to the National Register of Historic Places. That likely included the work Osborn produced after Muir’s death in 1914, including Osborn’s 1916 and 1921 introductions to “Hitler’s Bible,” Grant’s The Passing of the Great Race.

The sun was setting when my visit to Castle Rock was over.

I savored the scene. A purple sky faded to black as a seam of pink fire lit the horizon. The fading lavender light reflected off the snaking ribbon of the river, flowing through the dark silhouette of the rocky Highland fjord. The shadowed sawtooth profile of the Catskill mountains loomed far off in the distance. The horn of a train traveling along the river resounded through the valley, breaking what Muir might have called my religious-like “communion” with nature.

It was time to move on.

THE FREE LANCE NEEDS YOUR DONATIONS TO SURVIVE. DONATE HERE.

Sunset over the Highlands of the Hudson River Valley, West Point in the foreground, Catskills in the background, as seen from Woodsome Lodge, Castle Rock: Photo credit: JB Nicholas.